New Echota was the official seat of the Cherokee Nation’s constitutional government and the headquarters of its newspaper. The ATTTNT recognizes New Echota as the capital of a large Indigenous region overlapping multiple state jurisdictions. And it reassesses any previous tribal lands that touch its surface area, some of which now exist as reserves, state forests, or national parks, for possible contributions to reparation land trusts.

ATTTNT: a reparations infrastructure

Black land ownership in the US dropped from 15 million acres in 1910 to 3 million acres in 1970. In the 1960s, among the many activists who traveled to the South to fight for civil rights, some remained to expose forms of land theft and support the Black economy with cooperative organizations that linked the US South with the Global South. A constant undertow of white violence, abetted by government agencies, prevented further retention or restoration of land, but the detailed work, often in collaboration with HBCUs, identified land assets and developed land-holding organs and Black institutions to manage those resources.

When reconstructed, the work maps a scar across the US that does not try to cover over its ugliness and pain. Both recalling and foretelling, it tallies crimes beyond those of slavery while demonstrating how they are all also inextricably linked to future climate dangers. Tracking the transition from Dixiecrats to the Southern Republicans of Nixon and Reagan, this history also recalls recurring strategies that Trump has redeployed to craft the current polarized entrenchment. As it identifies these patterns of harm, the work simultaneously gives shape to reparations for the past and preparations for the future.

Returning to areas weighted with multiple traditions, the work begins to materialize a special infrastructure possessing the superabundant values of land, community, and education—an infrastructure as worthy of public investment as infrastructures of concrete and conduit. And it renews planetary solidarities from the 1960s and 70s with the capacity to address root causes of climate change and inequality. The work of these activists is a remarkable gift, as yet unopened, offering incalculable values to address an incalculable debt.

The project uses mapping and storytelling to make palpable this existing infrastructure—a network of HBCUs, Black institutions, and cooperative communities— as a framework to receive and manage multiple approaches to reparations. It is already positioned to redouble assets and address an incalculable debt with incalculable values related to land, community, and education. Given the coincidence of this Black Belt land with large federal land holdings, the project also identifies some immediate federal and private resources to thicken and enrich it.

These Black geographies probably don’t exist on a white mental map of the US South that might be decorated with obscene cartoons of manifest destiny, confederate glory, and stolen Indigenous imagery. The project begins by reclaiming three ribbons of public land—the Appalachian Trail (AT), the water route of the Trail of Tears (TT), and the Natchez Trace Parkway (NT). Previously scripted with white supremacist narratives, it is a 3000 mile long formation that might now have a reckoning with Black and Indigenous histories. ATTTNT is a kind of code for this loose aggregator or reference point for the patchy formations and stories that lie as satellites around it.

Beyond academic research, the site hopes to galvanize a campaign for this infrastructure of reparations land—assets deployed locally or remotely, organized in land holding organs invented during the period, and managed by the very black institutions that originally led the land activist movement.

Morgan State/Jackson State Partners: Samia Kirchner and Thomas Kersen

Website team: Keller Easterling, Alvin Ashiatey, Bianca Ibarlucea, Nicholas Arvanitis, Hima Goburru, Elis Huang, and Rebecca Mqamelo

Indigenous Sovereignties

Near the southern end of the AT, ATTTNT passes close to New Echota, the former capital of the Cherokee Nation—a huge area encompassing parts of today’s Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina and extending north to the Ohio River. In the 1830s, the state of Georgia defied Supreme Court rulings that gave rights to Indigenous people whenever those rights interfered with the conquest and possession of territory. President Andrew Jackson embodied the sentiments of the Monroe Doctrine and what would later be known as manifest destiny. He rose to prominence because of his campaigns as a leader of the Tennessee militia in the Creek War of 1813-14—a war that captured twenty-one million acres of Indigenous land in Alabama and Southern Georgia. An emboldened Georgia argued that it could ignore treaties and seize Indigenous land, and its treatment of Indigenous people was especially brutal. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, which ordered the westward relocation of Southern tribes to the new Louisiana territory, was a centerpiece of Jackson’s presidency. Indigenous nations protested the act as unconstitutional under both the US and Cherokee constitutions. While the first Supreme Court test, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) offered no relief, a ruling the next year, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) upheld Cherokee sovereignty and confirmed that treaties between the Cherokees and the US were binding. Ignoring the ruling, Jackson proceeded with a forced relocation of the five tribes—the Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, Chickasaw, and Choctaw—to the current state of Oklahoma along a network of routes that collectively became known as the Trail of Tears.

New Echota Capital

National Federation of Colored Farmers

National Federation of Colored Farmers

The National Federation of Colored Farmers (NFCF), established in 1922 to encourage cooperatives and collective organizing, set up its first local unit in Howard, Mississippi, near Tchula, in 1929. New of Black farmers and members in the Albany area appeared in NFCF newspaper The Modern Farmer, and NFCF work was reported in Negro World and other Black newspapers like The Defender. Promoting self-reliance and prosperity rather than populist political positions, the NFCF was closer to positions espoused at Tuskegee or to Garveyism, and it absorbed many UNIA members when that organization folded in the late 1920s. While hoping to coexist with whites, the NCFC, they quickly discovered that their tolerance would not be rewarded when Whites retaliated against the market competition.[1]

[1] "National Federation of Colored Farmers," The Modern Farmer, Vol. 1-21, 1929-39, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t1ck5xp0c&seq=5&q1=albany; Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice (Penn State University Press, 2014), 173-75; Jessica Gordon Nembhard, “African American Cooperatives and Sabotage,” The Journal of African American History, Winter/Spring 2018, Vol. 103, No. ½, Special Issue: National and International Perspectives on Movements for Reparations (Winter/Spring 2018), 65-90; Jarod Roll, “’The Lazarus of American Farmers’: the Politics of Black Agrarianism in the Jim Crow South, 1921-1938” in Debra A. Reid and Evan P. Bennett, Beyond Forty Acres and a Mule: African American Landowning Families Since Reconstruction (University Press of Florida, 2012), 132-152.

Farm Security Administration Projects

Inheriting projects from Division of Subsistence Homesteads, the Federal Emergency Relief Association, and the Resettlement Administration, they acquired nearly 2 million acres for between 140-150 cooperative community projects in the South. And while there were 25,000 most white cooperatives together with supporting cooperative banks, only thirteen all-Black communities survived racist bigotry in the North and the South to serve 1,150 Black families on 92,000 acres of land. Although there were additional scattered projects on 70-80,000 acres of land across the South. In some ways, the FSA seemed to be bestowing on Blacks cooperative practices for which they had long developed a tradition. And while New Deal programs did alleviate some white poverty in the South, they did little to relieve the truly dire situation that they had helped to exacerbate for Blacks.

Mileston

Flint River

Tennessee Farm Tenant Security

Tiverton

Allendale

Sabine

Tillery

Mounds

Townes

Lakeview

Desha Farms

Prairie Farms

Gee's Bend

El Malik

El Malik

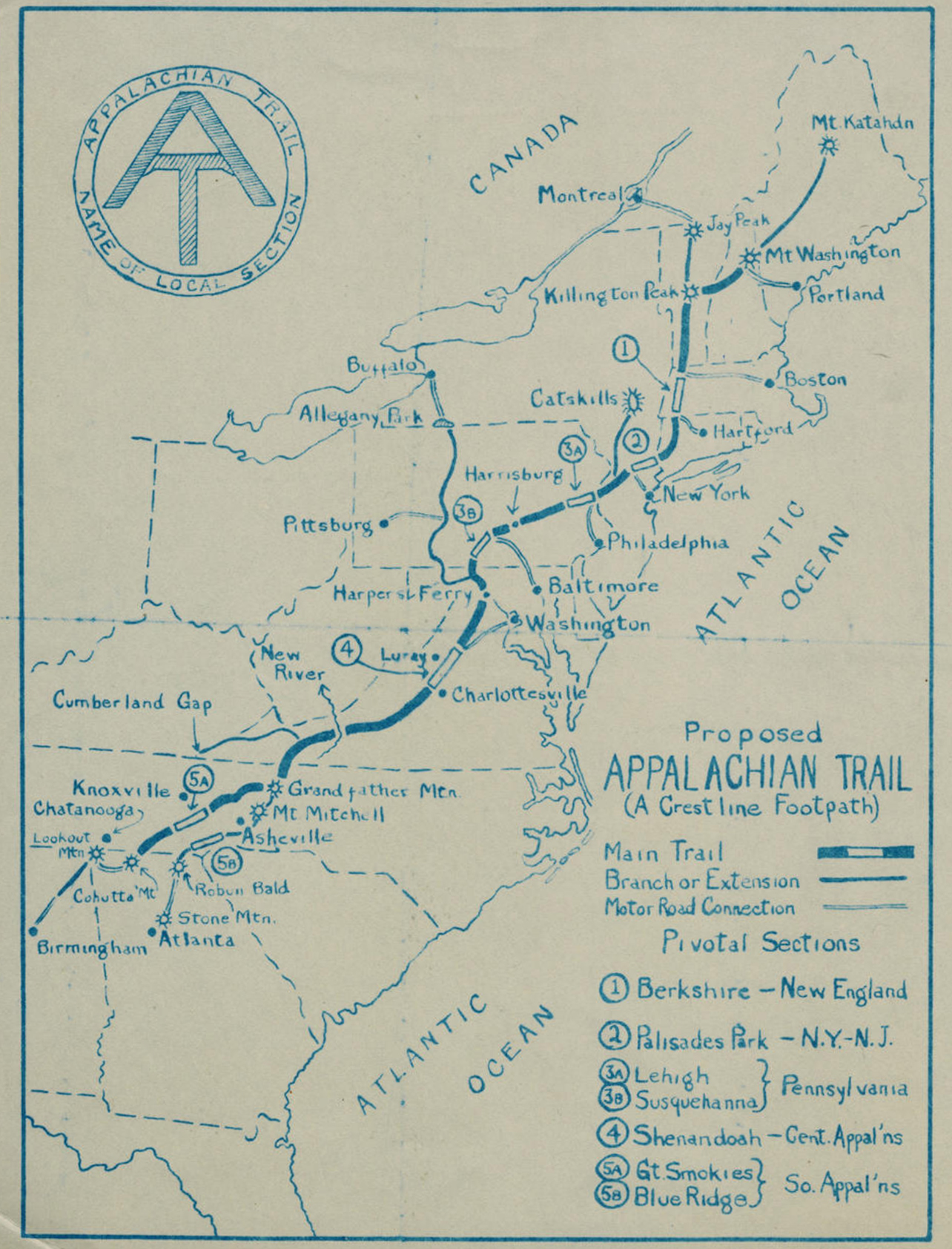

Appalachian Trail

In the 1920s, polymath Benton MacKaye envisioned a line across the United States that would organize land around the Appalachian mountains. Although today understood mainly as a scenic hiking route, the Appalachian Trail was initially meant to reorient the transportation and industry of the entire Eastern seaboard around land as a psychic resource for the nation and its labor in the postwar period. Remarkably, this 2,200-mile linear formation at the center of what MacKaye called a “super national” forest was completed in about fourteen years, with a boost from the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corp.

Appalachian Forest

The AT formation itself lies at lies at the center of a much larger region that it has helped to preserve, and today the Appalachian mountain range and forest is put forward as an example by those proposing to save half the planet for wildlife. In this accounting, the Appalachian joins other vast and largely intact ecoregions like the Boreal Forest, the Amazon River Basin, the Serengeti, and the Longleaf Pine forest that stretches from Virginia to Texas. Mapping these areas and claiming them in a cultural imagination contributes to their collective preservation and to the concrete recognition of planetary responsibilities that float above dominant jurisdictions.

ATTTNT reconceives and expands a 1993 proposal called ATTVA that was partially inspired by MacKaye. The 1993 ATTVA project made counterfeit USGS maps and aerial photographs that juxtaposed all the public land in the US with the waysides of the interstate highway—featureless strips of land that constitute the country’s largest public works project. It extended the Appalachian Trail into the nearly three hundred thousand acres of public lands assigned to the Tennessee Valley Authority. And it claimed this network of spaces as a diverse resource for many purposes.

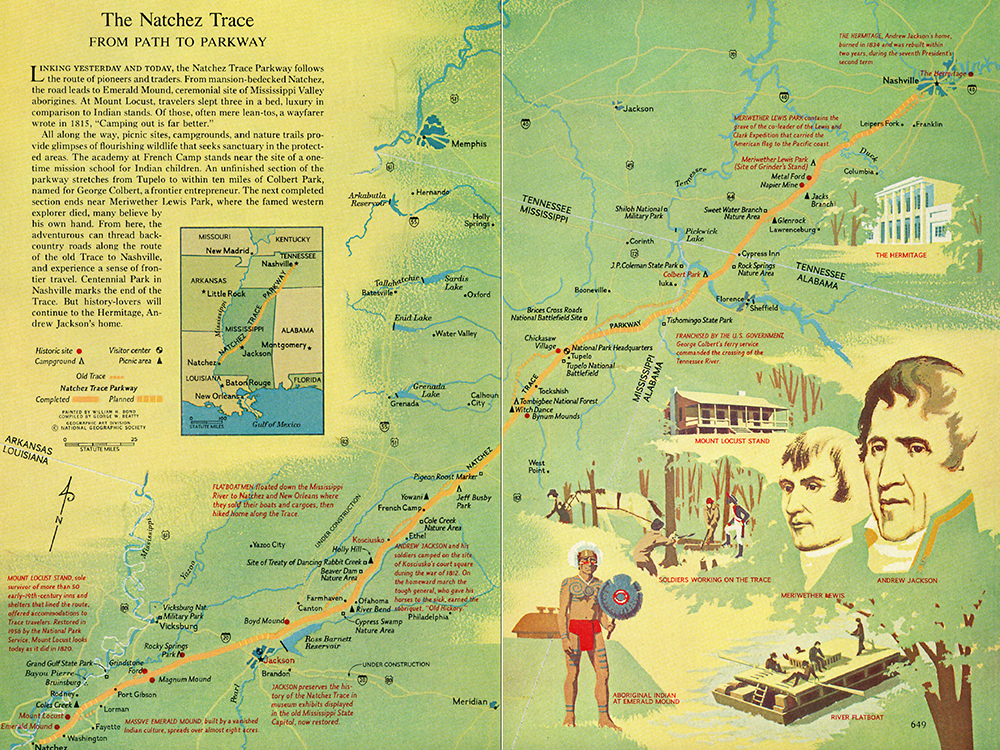

Natchez Trace Parkway

As the ATTTNT reaches its terminus in Natchez, it passes by sites that conjure other cringeworthy episodes marking the failure of whites to even begin to redress the incalculable debt of reparations. One of these sites in downtown Natchez is Ravennaside, the former home of Mrs. Roane Fleming Byrnes—the tireless promoter of the Natchez Trace Parkway. White Mississippians, among them the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), had long been campaigning for preserving or paving the Natchez Trace. In Ravennaside, Byrnes kept a map-filled “war room” for arm-twisting public officials and plying them with mint juleps. As the Trace Association president, she galvanized other NT enthusiasts, envisioning the NT as a monument to valorize the manifest destiny of westward expansion and the lives of Andrew Jackson and Meriwether Lewis while also recuperating the lost glory of the old South. Just at the moment that New Deal policies were exacerbating racism and bestowing token cooperative projects to Blacks who already had a long cooperative tradition, these whites were fighting for another history to launder that of the confederacy. These delusions aligned with those about celebrating the history of Indigenous people along the parkway. Similarly, Mrs. Byrnes was regarded as helpful in various charitable activities for Blacks in her community, but only in ways that did not disrupt the hierarchies of haves and have-nots reinforcing white myopia. In 1939, a year after the NT had managed to acquire some initial New Deal funding, the DAR refused to allow the famous contralto Marian Anderson to sing at their DC headquarters because of her race, a move that prompted Eleanor Roosevelt to cancel her membership. If proponents of a commemorative parkway with no urgent function managed to assemble over fifty thousand acres for the rights-of-way, can there be a movement to assemble state, federal, and municipal lands and even private parcels for conversion to reparations trust land? Many landowners have already designated sections of their land for conservation easements in exchange for tax breaks or other benefits. Additional small incentives may encourage fully relinquishing the land. A number of anti-capitalist investment consultants are also now helping investors to distribute rather than hoard their wealth, in landholding organs that include land trusts. Looking for another kind of resource and justice in the failures of capital and governance, the ATTTNT also develops protocols for assessing land that is exhausted, bankrupt, over-subsidized, or stagnant because of retiring farmers, debt, or disputes among property heirs.

Ravennaside

As the ATTTNT reaches its terminus in Natchez, it passes by sites that conjure other cringeworthy episodes marking the failure of whites to even begin to redress the incalculable debt of reparations. One of these sites in downtown Natchez is Ravennaside, the former home of Mrs. Roane Fleming Byrnes—the tireless promoter of the Natchez Trace Parkway. White Mississippians, among them the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), had long been campaigning for preserving or paving the Natchez Trace. In Ravennaside, Byrnes kept a map-filled “war room” for arm-twisting public officials and plying them with mint juleps. As the Trace Association president, she galvanized other NT enthusiasts, envisioning the NT as a monument to valorize the manifest destiny of westward expansion and the lives of Andrew Jackson and Meriwether Lewis while also recuperating the lost glory of the old South.

Just at the moment that New Deal policies were exacerbating racism and bestowing token cooperative projects to Blacks who already had a long cooperative tradition, these whites were fighting for another history to launder that of the confederacy. These delusions aligned with those about celebrating the history of Indigenous people along the parkway. Similarly, Mrs. Byrnes was regarded as helpful in various charitable activities for Blacks in her community, but only in ways that did not disrupt the hierarchies of haves and have-nots reinforcing white myopia. In 1939, a year after the NT had managed to acquire some initial New Deal funding, the DAR refused to allow the famous contralto Marian Anderson to sing at their DC headquarters because of her race, a move that prompted Eleanor Roosevelt to cancel her membership.

If proponents of a commemorative parkway with no urgent function managed to assemble over fifty thousand acres for the rights-of-way, can there be a movement to assemble state, federal, and municipal lands and even private parcels for conversion to reparations trust land? Many landowners have already designated sections of their land for conservation easements in exchange for tax breaks or other benefits. Additional small incentives may encourage fully relinquishing the land. A number of anti-capitalist investment consultants are also now helping investors to distribute rather than hoard their wealth, in landholding organs that include land trusts. Looking for another kind of resource and justice in the failures of capital and governance, the ATTTNT also develops protocols for assessing land that is exhausted, bankrupt, over-subsidized, or stagnant because of retiring farmers, debt, or disputes among property heirs.

Andrew Jackson

The Natchez Trace Parkway was envisioned as something like a monument to valorize the manifest destiny of westward expansion and the lives of Andrew Jackson and Meriwether Lewis while also recuperating the lost glory of the old South.

Southern Tenant Farmer's Union (STFU)

In 1934, Blacks and whites also joined forces to create the socialist-based Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union (STFU), another organization that along with one of its founders H. L. Mitchell, survived to influence the movements of the 1960s and 70s. They were especially active organizing strikes against evictions and white terror in counties along the Mississippi River in Mississippi and Arkansas. But the undertow of the Depression and the discriminatory distribution of resources to whites would soon challenge this separatists, self-help positions of Garveyites and NFCF members many of whom joined forces with the STFU. The STFU together with the Socialist Party of America and a Christian Socialist group led by Reinhold Neibuhr, also established cooperative interracial colonies in the same areas of the northern Mississippi Delta. With support from Quaker volunteers, Eleanor Roosevelt and other luminaries, they established Delta Farms (later renamed Rochdale) in 1936, near Hillsdale and Providence Farms, near Cruger, about an hour and half south in 1938. The STFU towns were interracial but segregated so as not to attract violence.

Providence Cooperative Farm

Delta Cooperative Farms (Rochdale)

Poor People's Corporation

White Station

West Point

Tchula

Shelby

Shaw

Prairie

Mount Olive

Mount Nebo

Cleveland

Canton

Aberdeen

McComb Leather Cooperative

Liberty House Outlet

Cooperation Jackson

Cooperation Jackson, established in 2014 and included in the dossier accompanying this book, is a network of efforts that applies civil rights era activist forms to planetary concerns. Facing ongoing repression in the South, and inspired by Jackson’s activist history, Cooperation Jackson reoccupies the sovereignties of the Kush and the RNA capital El Malik. The contemporary Jackson-Kush plan works on multiple fronts. The Malcolm X Grassroots Movement (MXGM) and the New Afrikan People’s Organization (NAPO) partners with the FSC, the Southern Grassroots Economies Project, and the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA), among many others. They foster Black political power with assemblies and campaigns to place elected officials, they generate solidarity in a broad swath of the US, and they work to build a broad “Solidarity Economy.” Joining anti-neoliberal activist efforts around the world, the solidarity economy “describes a process promoting cooperative economics that promote social solidarity, mutual aid, reciprocity and generosity.” Extending their global reach, they liken regional formations like the Kush and Black Belt to regional cooperatives like the Mondragon Federation of Cooperative Enterprises, based in the Basque region of Spain and the Emilia Romagna region of Italy, both of which are also included in the dossier for this publication. Cooperation Jackson organizes gardens, a restaurant, community activities and education efforts among many other projects in the city of Jackson and its environs. It has also established the Jackson Human Rights Institute for training and organizing. Cooperation Jackson is a central case study for many who look to a horizon of change where the logics of capital are outflanked by a spectrum of cooperative forms and where white, right-wing politics no longer dominates the Southern US. Like Gar Alperowitz, critical theorist Bernard E. Harcourt cites Cooperation Jackson as evidence of an increase in cooperative forms. New York Times columnist and author Charles M. Blow, in both a book and a film, references Cooperation Jackson as one magnet for a reverse Black migration from the North to the South to create a voting bloc that reclaims electoral power for Black leadership.

Cooperation Jackson Headquarters

Nation of Islam Farms

Forkland, Alabama

Pell City, Alabama

Muhammad Farms

New Communities, Inc.

In 1968, near Albany, Georgia, Slater King and Charles Sherrod established New Communities, Inc. (NCI),—the first community land trust. Situated near Koinonia and one of several Nation of Islam (NOI) farms established in Georgia and Alabama in the 1960s and ’70s, NCI was part of a remarkable cluster of community experiments. Its founders later claimed that the community land trust was a form based on Indigenous conceptions of land, moshavs, Mexico’s ejidos, the Gramdan movement, and Ujamaa. The claim reflected the milieu of the time and the solidarities between civil rights, Pan-African, Non-Aligned, and Tricontinental movements that might inspire similar planetary solidarities today. Community land trusts may offer a convenient land holding organ reparation land. Since they pool urban or rural land to be managed by a group of people, community land trusts are larger, more complex, and less digestible in gentrifying real estate processes. They can offer more cohesion and stability within communities threatened by dispossession. They have also recently become tools for auto-constructed or informal settlements to collectively reorganize their land for remediation and infrastructure building. There is currently a globally networked movement to create community land trusts around the world.

Smithfield, Georgia

Interracial Intentional Communities

In addition to the communities associated with the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, other interracial Christian communities attempted to establish outposts in the South. Macedonia, Georgia (1936), Little River Farm, South Carolina (1940); and Koinonia, Georgia (1942) were among these. These joined other intentional communities started between the 1930s to 1950s that were practicing communalism, often colored by religion. They joined communal projects of the Catholic Worker Movement founded in the 1930s, like Tivoli, New York; Sunrise Community, Michigan, (1933) organized by a Jewish group; Celo Community, North Carolina (1937); the Quaker community of Vale, Ohio (1940); Hutterite communities like Zion’s Order, Missouri (1952), the Mennonite community Reba Place, in Evanston Illinois (1957). A number of communities inspired by the writings of Georgist community theorist Ralph Borsodi in the 1930s and 40s were also sometimes associated, and they included Baylard, Bryn Gweled, and Tanguy Homesteads in Pennsylvania, Van Houten Fields and Skyview Acres in New York, May Valley Cooperative Community in Washington State and Melbourne Village in Florida.

Little River Farm, South Carolina

Macedonia, Georgia

Koinonia, Georgia

Clarence Jordan and Martin England, a missionary on furlough from Burma founded Koinonia in 1942 because they were interested in cooperative farming, improving the lives of poor Blacks, living up to their beliefs, and evangelizing about Christianity. Jordan said, "We want to be humble, rural missionaries."[1] They chose a site in rural Georgia in which Black outnumbered Whites two to one. When Jordan and England and their wives first arrived at Koinonia, they took turns pulling the plow, shared all resources equally, and began contacting their neighbors. Koinonia, meaning community in Greek, aligned with Jordan’s reliance on Greek translations of the Bible and tried to recreate the communalism of the early church.

An isolated enclave in the deep Jim Crow South, Koinonia’s interracial practices went unchallenged until they began to disrupt the habits of segregation or seemed to test a desegregation mandate from the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling. From the mid 1950s on, the community endured KKK shootings, and bombings. Their children were beaten up at school. Their lives were continually threatened. In addition to legal attacks and accusations of communism, an economic boycott of Koinonia’s farm goods brought the community to its knees. The community considered merging with other religious enclaves but could not reconcile differences with them, and they even attempted to relocate or develop satellite colonies. They shifted from row crops to cattle, started growing grapes, and also developed a mail order business that shipped pecans, among other things, all over the country.[1]

[1] Tracy Elaine K'Meyer, The Story of Koinonia Farm: Interracialism and Christian Community in the Postwar South (University of Virginia Press, 1997), 82-92; Jim Auchmutey, The Class of 65: A Student, a Divided Town, and the Long Road to Forgiveness (Public Affairs, 2015); "Bi-Racial Farm Unit Buying Jersey Site" New York Times, April 5, 1957; Slater King to Clancy Sigal, May 30, 1963, Slater King Papers, Fisk University, Box 2, Fld. 10.

[1] Tracy Elaine K'Meyer, The Story of Koinonia Farm: Interracialism and Christian Community in the Postwar South (University of Virginia Press, 1997), 37.

Black Refuges during the Civil War

The Union Army established places of refuge for freed slaves during the war. Notable among these was a swath of land along the eastern coast reserved as reparation land under General Sherman's Field Order No. 15 until the post-war government reneged on the deal and gave the land back to planters. Davis Bend, near Vicksburg on the Mississippi River was also the site of a Black community that eventually migrated to the Mississippi Delta area to found the independent Black town of Mound Bayou in 1887.

Field Order No. 15

General Sherman’s Field Order No. 15 explicitly reserved 40 acres and a mule for former slaves on 400,000 acres of land within a thirty mile wide swath stretching 400 miles from Charleston to St. John’s River.

Davis Bend

The Union Army also established a place of refuge on the Mississippi at Davis Bend—the plantation land of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his older brother Joseph Davis on the Mississippi near Vicksburg. The house the Jefferson Davis plantation, Briarfield, was used as the first headquarters of the Freedmen's Bureau. The library on Joseph Davis' Hurricane Plantation, was also saved. Influenced by the ideas of socialist reformer Robert Owen but motivated by potentials for greater productivity and profit, Joseph Davis attempted a bizarre utopian experiment in which his slaves would be given education and allowed self governance. His slave, Benjamin Montgomery managed the plantation. Montgomery and his sons returned before the end of the Civil War, started a community at Davis Bend with military protection, and made plans to buy both plantations. The community flourished until storms, a cotton industry decline, financial trouble and Montgomery's death. One of his sons, Isaiah Montgomery led a group to buy land on a railroad line at Mound Bayou in the Mississippi Delta.

Mound Bayou

Mound Bayou, an independent Black community established in 1877, that repeatedly resurfaced as a historical marker. Mound Bayou and surrounding counties hosted multiple chapters of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association between 1920-1935. The area continued to attract multiple cooperative experiments in the civil rights and post civil rights periods.

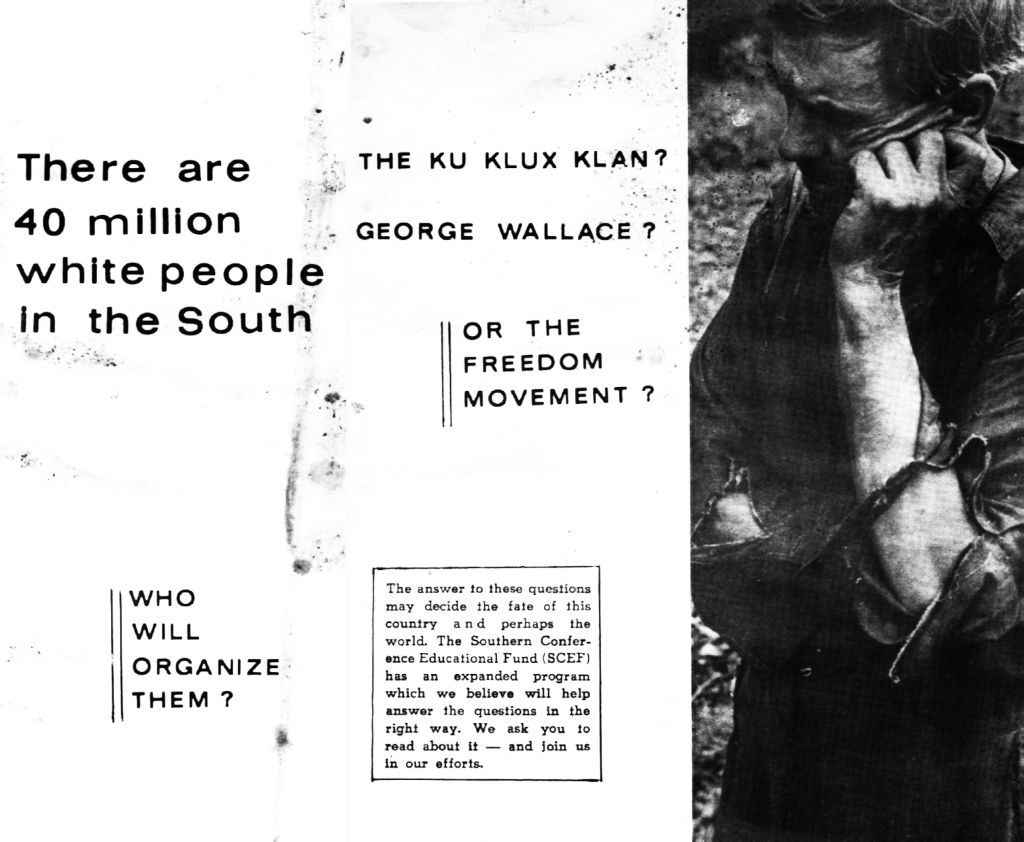

Southern Student Organizing Committee

For the Southern Student Organizing Committee, Ella Baker, Anne Braden, Bob Moses, Myles Horton from Highlander Folk School, and Todd Gitlin from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) were guiding forces. Anne Braden had long been trying organize white students, and she though SSOC should accept Black leadership and serve as an arm of SNCC. She saw SSOC as a continuation of a longer history of interracial collaboration around Populist labor organizing. She had gotten Bob Zellner, a white southerner a campus organizers, the first white staff position at SNCC. Zellner was among the first cohorts to face violence in Mississippi or get arrested in Albany. Both white and Blacks were wary and SSOC partnership. The whites were concerned that SNCC’s radical positions might have it difficult to approach more conservative whites. Bob Moses of SNCC, was concerned that Blacks might lose the “the first thing that we’ve ever had that belongs to us.” Other Blacks in the movement thought that whites should work separately on their own white community. While claiming to be tentative about the perceived radicalism is SNCC, SSOC did join forces with SDS, a group that was more rigidly ideological, because they hoped it that the nationally established intellectually sophisticated organization would lend them weight.

SSOC Nashville meeting

A group of Nashville students organized a meeting on the weekend of April 3-5, 1964, in Nashville and another a few weeks later in Atlanta in May to form the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC).

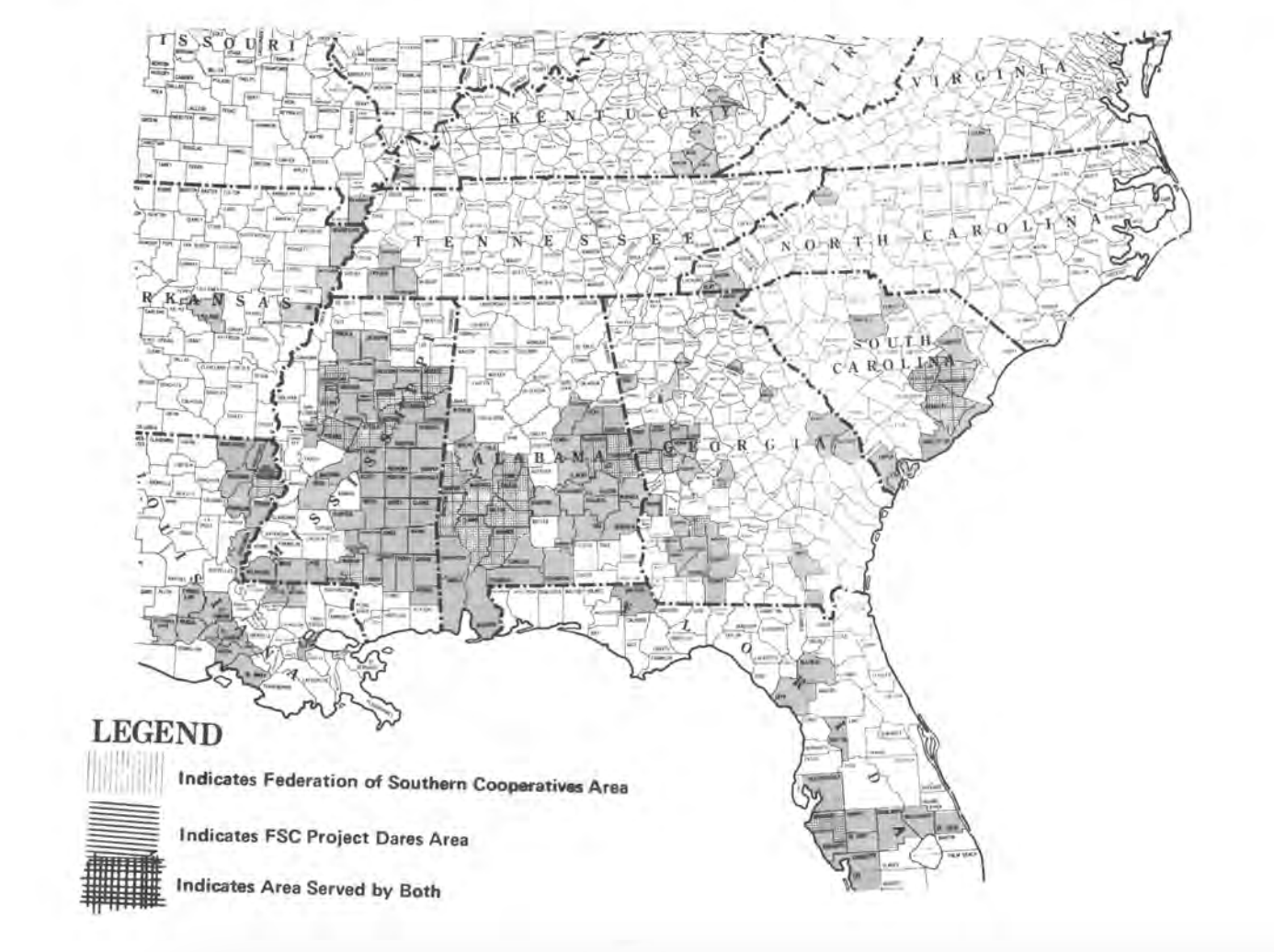

Federation of Southern Cooperatives 1967 Members

After passage of the Civil Right Act and the Voting Rights Act in 1964 and 1965, cooperatives were emerging all over the South as a way to organize the next phase of activism after the Civil Rights Movement. In 1967, 22 such coops from 10 states joined to create the Federation of Southern Cooperatives to be a clearinghouse for education, training, marketing, research, finance, collective knowledge, and technical expertise, to provide member services like insurance and health care, and to be an advocate for Black farmers and rural cooperatives. With funding from the Office of Economic Opportunity and guidance from National Sharecropper Fund, the Southern Regional Council, and the Cooperative League of the USA, they established an central office in Atlanta to serve the region. Later, the Federation moved its headquarters to Epes, Alabama where it created a Rural Training Center. By 1970, there were over 100 member coops. The Federation of Southern Cooperatives is still in operation today representing over 10,000 Black farmers in the South. Twenty of the coops listed in the original articles of incorporation from 1967 are mapped here.

Southern Farmers Cooperative Association

Mid-South Consumers Oil Cooperatives

Producers Cooperative

Grand Marie Vegetable Cooperative

Credit Union

Farm Machinery Cooperative

Fairfield Vegetable Producers

Poor Peoples Cooperative

Middle Mississippi Farmers Cooperative

Southern Consumers Cooperative

Working in and around Lafayette, Louisiana, Father Albert McKnight discovered that he could not minister to his congregation without attending to their economic survival. He first set up a buying cooperative after studying the Antigonish movement at the Coady Institute in Nova Scotia during the summer of 1960. Every member of church contributed give dollars to buy goods wholesale that would then be sold for a small markup, and members divided the profits. The idea spread to surrounding areas. In September of 1961, the McKnight led a group to form the Southern Consumers Cooperative (SCC) with elected delegates from surrounding towns. By 1963, SCC had 550 members and groups working in 16 surrounding towns and capital totally $13,000. One of the first enterprises was the Acadian Delight Bakery in Lake Charles Louisiana, which primarily sold fruitcakes. McKnight then helped communities to form credit unions.

In 1964, SCC formally incorporated, but more importantly, November 24, it received word that they had been awarded the inaugural grant of $25,000 from Office of Economic Opportunity—an initial marker of LBJ’s war on poverty. The SCC could now claim members of 650 family and capital totaling more than $19,000.[1] Southern Consumers Cooperative was composed of three entities—the Southern Consumers Education Fund, a non-profit training arm, People’s Enterprise, a small loan company, and Acadian Delight Bakery. SCEF as non-profit tax exempt organization, also began to sponsor Head Start programs in Louisiana.[2]

When the first check was presented on December 22, McKnight and the SCC presented fruitcakes to Sargeant Shriver and President Johnson. The SCC later joined the Federation of Southern Cooperatives.

[1] “First Help in Poverty War to Lafayette Firm,” Morning Advocate, December 23, 1964. A News letter suggests that the Papers of the Southern Regional Council, Reel 47, Location, 1639, 1639.

[2] Father Albert Joseph McKnight, Whistling in the Wind (Smashwords Edition, 2011).

Housing Cooperative

Textile Cooperative

Harris County Farmers Cooperative

NEJA Federal Credit Union

C & C Grocery

Hale County Baking Cooperatives

Freedom Quilting Bee

Greenala Citizens Federal Credit Union

Southwest Alabama Farmers Cooperative

Epes Rural Training Center

National Sharecroppers Fund

NSF Demonstration Farm, Burke County, GA

Tennessee Valley Authority

Cooperative Utilities

The Trail of Tears segment of the ATTTNT reassesses land surrounding the Tennessee River that was acquired by the TVA during the New Deal. The TVA was responsible for land dispossession in the region, and its dam-building model was exported to developing countries around the world with environmentally disastrous effects. Still, environmental advocates reference the TVA because it represents the political will to acquire a nearly three-hundred-thousand-acre watershed for a publicly owned utility with thousands of employees and millions of customers.

Advocates for community-owned infrastructure, like political economist Gar Alperovitz, point out that the TVA’s huge public collective, like the electrical co-op in Nebraska or the state bank in North Dakota, resides in a Red state.[1] Many state governments that may rail against progressive energy, cooperative forms, or government subsidies nevertheless rely on cooperatives and receive enormous government subsidies from agencies like the US Department of Agriculture.

Raccoon Mountain, directly adjacent to the ATTTNT, is one of the largest hydroelectric plants in the US. [KE1] The plant works with other renewable energy sources to generate power from movement between two levels of water storage while also providing a park and recreation area. ATTTNT links this successful climate narrative to the cultural persuasion about reparations.

[1] Gar Alperowitz and Thomas M. Hanna, “Socialism, American Style,” New York Times, July 23, 2015; Gar Alperowitz, What Then Must We Do? Straight Talk about the Next American Revolution (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2013).

Freedmen towns

After the war, freedmen towns and other Black communities and or family compounds located in the Black Belt—a crescent of fertile land stretching from Virginia to Texas. For a few years from 1865 to 1872, the Freedman’s Bureau helped former slaves buy land and establish educational institutions. Many of the 4.4 million former slaves necessarily organized land and work cooperatively for protection and pooled resources. Many of these locations are unmarked and unrecorded, although contemporary researchers are beginning to map southern states thickly populated with freedmen towns.

Free Hill, Tennessee

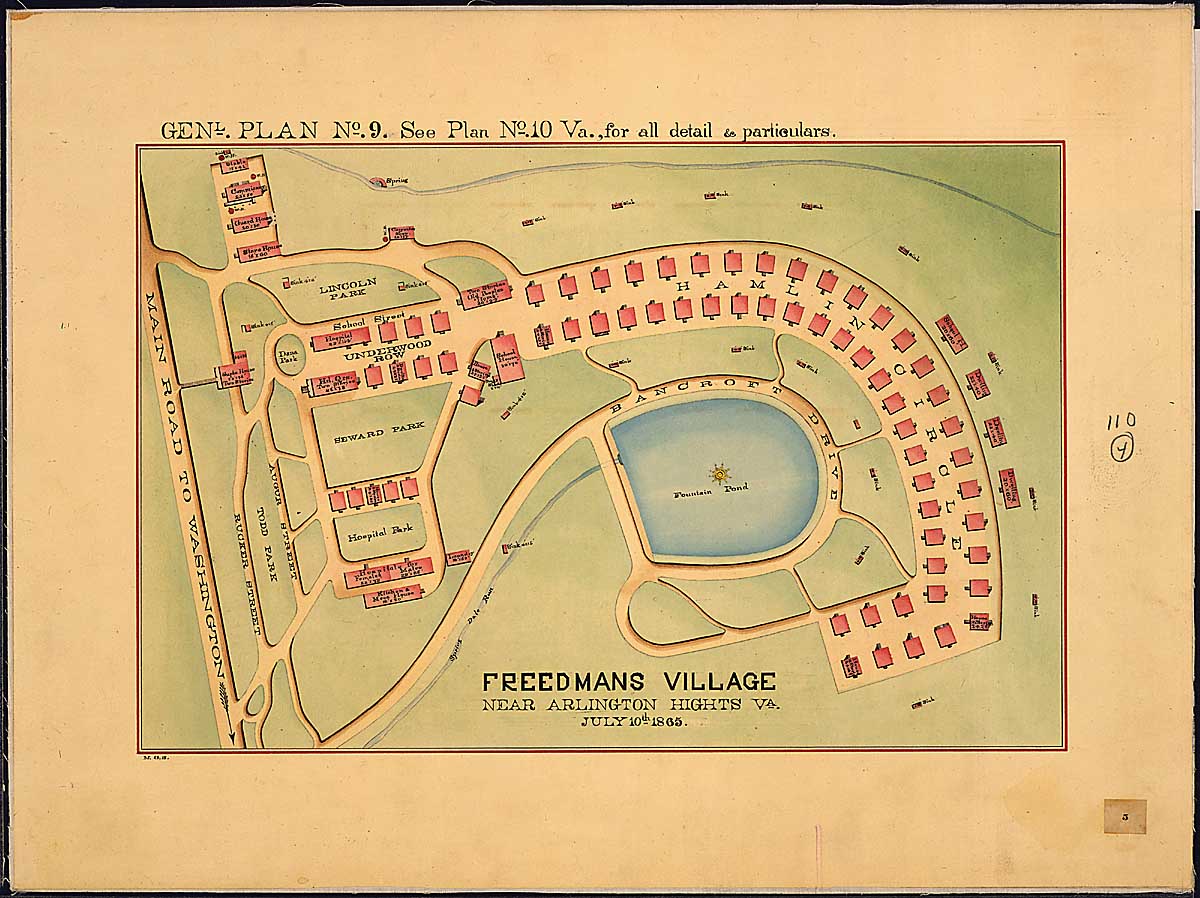

Freedmen's Village, Virginia

This is an image of Freedman's Village

Harbor Island, Maine

Princeville, North Carolina

Mossville, Louisiana

Mitchellville, South Carolina

Oscarville, Georgia

Pennick, Georgia

Pin Point, Georgia

Scotlandville, Louisiana

Roanoke Island Freedmen's Colony, North Carolina

Unionville, Maryland

Promised Land, South Carolina

Little Egypt, Texas

Hayti, North Carolina

Clearview, Oklahoma

Eatonville, Florida

Fargo, Arkansas

Bethania, North Carolina

Chubbtown, Georgia

Hobson City, Alabama

Africatown, Alabama

Fanny Lou Hamer's Freedom Farm Corporation

Freedom Farm Corporation, Ruleville, Mississippi

Mt. Beulah

Mt. Beulah was a conference center in an abandoned HBCU that hosted countless planning meetings for the civil rights movement.

Mt. Beulah

Emergency Land Fund

Robert S. Browne, a global economist who had written an influential article on Black separatism, established the Black Economic Research Center (BERC) in 1969 in New York City and the Emergency Land Fund (ELF) in 1971 with offices throughout the South. Replacing white expertise with Black expertise, Browne, Jesse Morris, founder of the Poor People's Corporation, and Joe Brooks, former planner for the Republic of New Afrika, together with a consortium of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBUCs) provided cogent surveys of Black land loss and future plans for land retention and reparations. Reaching back to Reconstruction, they exposed failed federal land policies, tax traps, discriminatory lending by government agencies, and the legal tricks that whites used to force partition sales on heirs property—property owned by multiple descendants. They developed pilot projects and disseminated information in a newspaper called *Forty Acres and a Mule.* ELF merged with Federation of Southern Cooperatives in 1985.

Field Office, Charleston, South Carolina, 134 Meeting Street

Field Office, Jackson, Mississippi

Black Land Service, Elf Affiliate in Frogmore, South Carolina

Field Office, Montgomery, Alabama, 352 Dexter Avenue

New York Office Black Economic Research Center, 112 West 120th Streeet

Atlanta, Georgia Office 836 Beecher Street NW

Parcel Research

Davis Bend

South and west of Jackson, Davis Bend, formerly the plantation land of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his brother Joseph Davis, land was set aside for former slaves and occupied with successful experiments. The Jefferson Davis plantation became a site of the Freedman’s bureau. Before the war Joseph Davis attempted an strange experiment that, while based of socialist reformer Robert Owen, was actually motivated by potentials for greater productivity and profit. Land was returned to its previous confederate owners after the war. Former slaves bought land on the Joseph Davis plantation and established a Black community. But after devastating storms and other obstacles, the community migrated to Mound Bayou in the Delta to establish one of the most prominent all-Black towns.

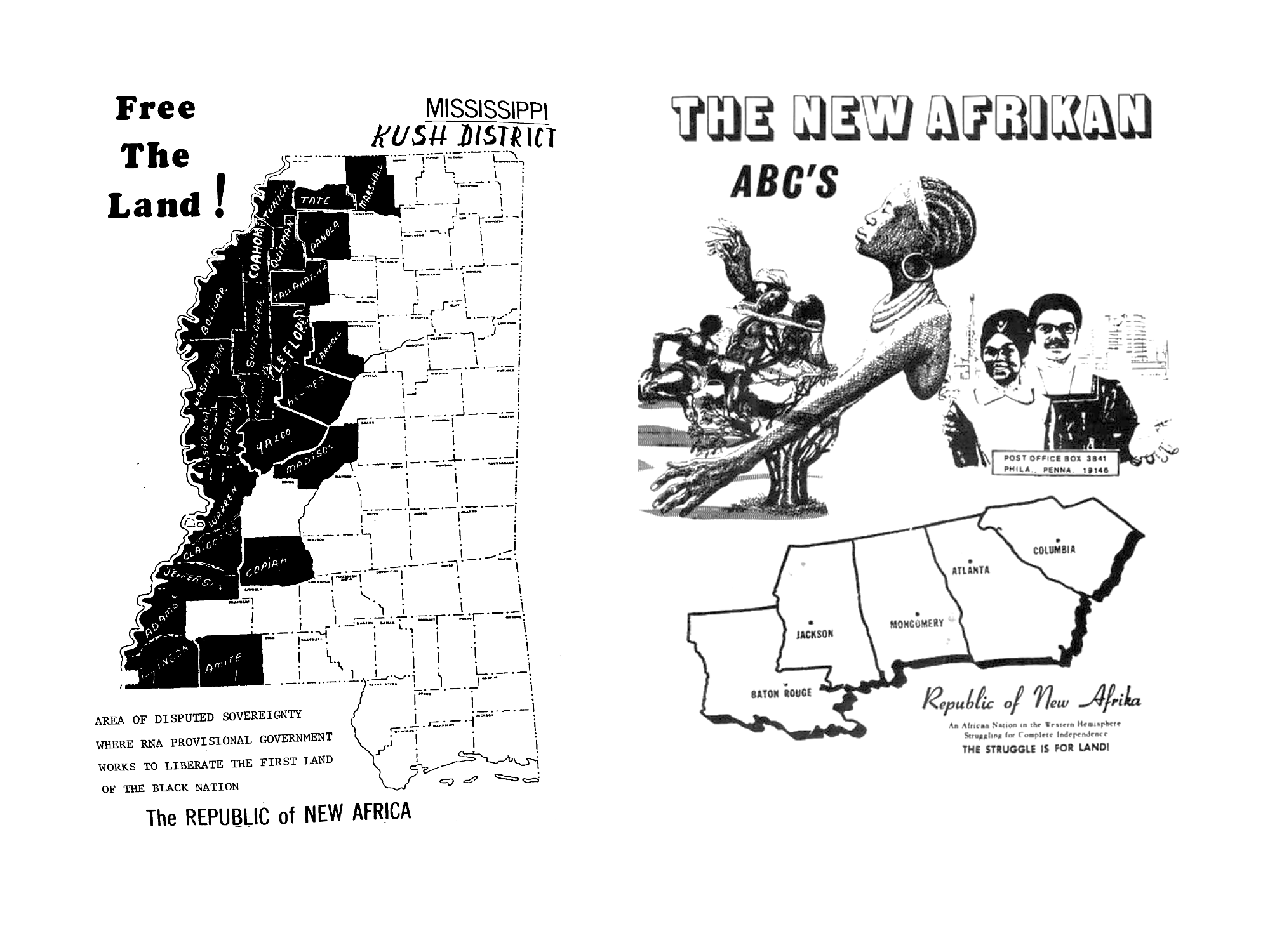

Republic of New Africa

In the 1960s and 70s, solidarities between civil rights, Pan-African, Non-Aligned, and Tricontinental movements linked the US South and the global. The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) claimed the Kush counties that were most heavily populated by Blacks to be the first lands liberated for a new separatist nation, the 1968 Republic of New Afrika (RNA). They claimed the states Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina for this new nation to be organized around Tanzanian President Julius K. Nyerere’s socialist principles of Ujamaa. Robert F. Williams—one of many exiled COINTELPRO target advocating from various outposts in Cuba, Ghana, Tanzania, China, and Vietnam—was selected to be president of the nation. Near Edwards, Mississippi, west of Jackson. RAM attempted to establish the capital city of El Malik, in 1971. They requested reparations of four hundred billion dollars from the US government, money that would be put towards developing cooperative communities.

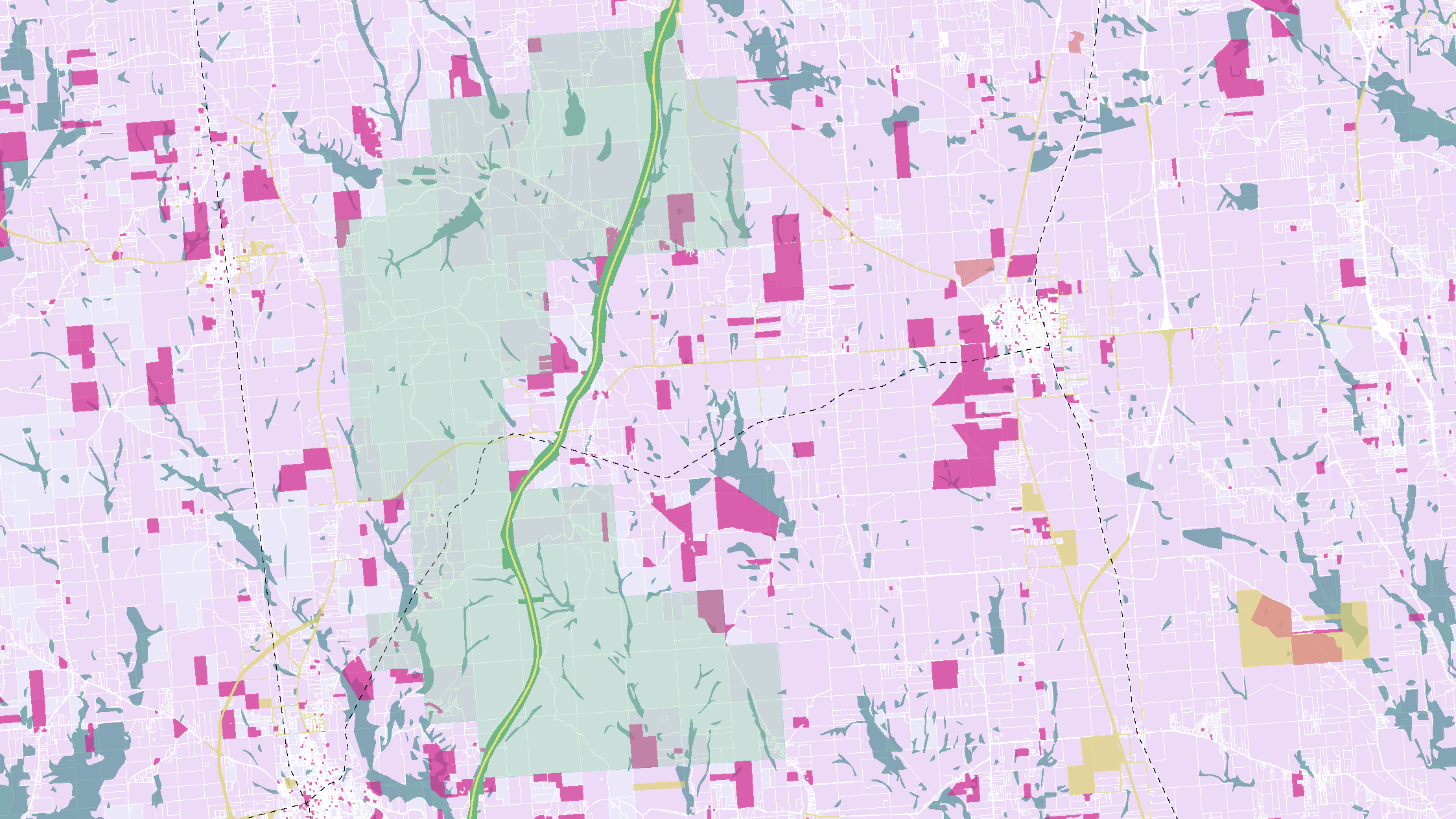

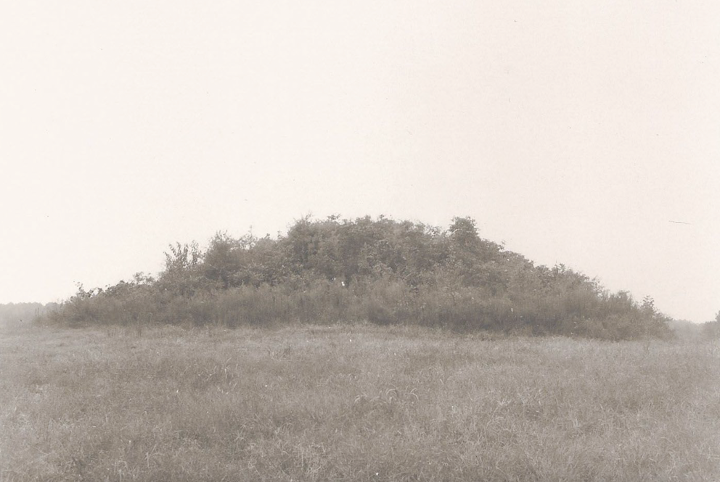

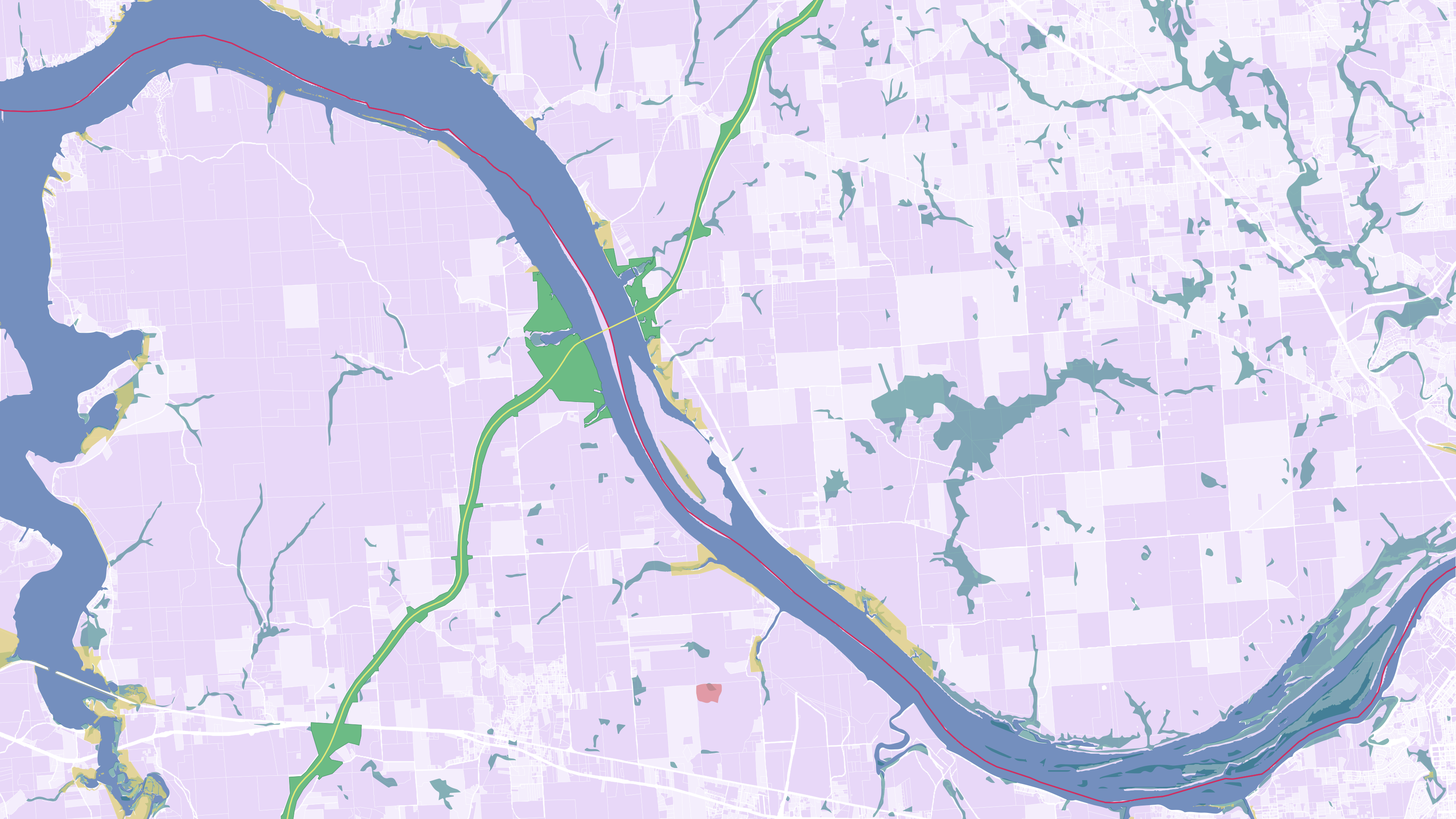

Tombigbee Forest

South of Tupelo, Mississippi, the Tombigbee National Forest is just one of many public land holdings appearing along the ATTTNT. Tombigbee preserves the Owl Creek Mounds—Indigenous formations dating back to between 1100 and 1200 CE. A few of the mounds made by the twenty-one tribes who lived in what is now Mississippi. Some were flattened by agriculture, while others are preserved as part of a fiction that downplays the initial theft of Indigenous land and portrays a magnanimous white appreciation of Indigenous culture. Abandoned rail lines (dotted line) also pass through the southern end of Tombigbee Forest and cross the ATTTNT. They recall the post-Civil War “emancipation circuit” that Thulani Davis describes—a network of movement for labor, goods, music, and ideas that often followed rail lines. Magenta indicates sites for heirs property research. Teal indicates wetlands.

TVA_NT juncture

The Trail of Tears segment of the ATTTNT also reassesses land surrounding the Tennessee River that was acquired by the TVA during the New Deal.

HBCU_1890

West Virginia State University Copy

Virginia State University Copy

University of Maryland Eastern Shore Copy

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Copy

Tuskegee University Copy

Tennessee State University Copy

Southern University and A & M College Copy

South Carolina State University Copy

Prairie View A & M University Copy

North Carolina A & T State University Copy

Lincoln University Copy

Langston University Copy

Kentucky State University Copy

Fort Valley State University Copy

Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University Copy

Delaware State University Copy

Central State University Copy

Alcorn State University Copy

Alabama A & M University_

Jackson Organizations